Joyce the

Ringer Brit once tried to explain what it was like for a godless atheist like herself to take a class at the Yale Divinity School. "We were doing Plato," she said, "but the professor kept making weird assumptions about students beliefs. I remember him saying, 'I'm going to assume that we all accept Plato's argument for the immortality of the soul,' and it was all I could do not to raise my hand and explain that that's not how we read Plato downtown." As a religious studies major I took plenty of classes at the Div School and never minded their teaching style, but I have to be sympathetic to Joyce. After all, when you've got a line as good as "That's not how we read Plato

downtown," how can you keep from singing?

To add to her catalogue of Outer Borough Readings of Plato, I'll mention something that occurred to me as I went back through the

senior essay (read it! I've fixed the typos!). The

Symposium describes an eros that (a) transcends the physical, (b) is homosexual, and (c) forms the basis of education. It meant a lot to Oscar Wilde that a figure as august as Plato considered these three aspects to be inseparable, and he wasn't the only gay Victorian to feel that way. Today we think of Plato's reputation as an unimpeachable constant, but, in 1834, J. S. Mill

lamented that ten years of Oxford graduates didn't include more than six men who had so much as skimmed the dialogues. In the mid-nineteenth century, there was a feeling of

rediscovery about Plato, and gay men felt they had a special claim on him. That's why it's funny to me that the pedagogic eros Plato talks about has become the property of straight people.

When I use the phrase "pedagogic eros," I don't just mean that smart is sexy, although I could tell a funny story about the time I kissed a boy I shouldn't have simply because he could recite every also-ran ticket in American history, president

and vice-president. It's hard to put exactly what I mean, or, more accurately, it's hard to put it any way without sounding suggestive. Bill Deresiewicz tried

here and I can't expect to do better:

. . . the professor-student relationship, at its best, raises two problems for the American imagination: it begins in the intellect, that suspect faculty, and it involves a form of love that is neither erotic nor familial, the only two forms our culture understands. [...] Teaching, Yeats said, is lighting a fire, not filling a bucket, and this is how it gets lit.

. . . I’m not saying anything new here. All of this was known to Socrates, the greatest of teachers, and laid out in the Symposium, Plato’s dramatization of his mentor’s erotic pedagogy. We are all “pregnant in soul,” Socrates tells his companions, and we are drawn to beautiful souls because they make us teem with thoughts that beg to be brought into the world. The imagery seems contradictory: are we pregnant already, or does the proximity of beautiful souls make us so? Both: the true teacher helps us discover things we already knew, only we didn’t know we knew them. The imagery is also deliberately sexual. The Symposium, in which the brightest wits of Athens spend the night drinking, discoursing on love, and lying on couches two by two, is charged with sexual tension. But Socrates wants to teach his companions that the beauty of souls is greater than the beauty of bodies. Can there be a culture less equipped than ours to receive these ideas? Sex is the god we worship most fervently; to deny that it is the greatest of pleasures is to commit cultural blasphemy.

. . . The Socratic relationship is so profoundly disturbing to our culture that it must be defused before it can be approached. [D's essay begins by unpacking the stereotype of the "alcoholic, embittered, writer-manqué English professor who neglects his family and seduces his students."—CSB] Yet many thousands of kids go off to college every year hoping, at least dimly, to experience it. It has become a kind of suppressed cultural memory, a haunting imaginative possibility. In our sex-stupefied, anti-intellectual culture, the eros of souls has become the love that dares not speak its name.

From Wilde in the nineteenth century to Deresiewicz quoting Wilde in the twenty-first, pedagogic eros has been misunderstood. That's fine; if you've known it, you don't care. The more important question, as Deresiewicz suggests, is where to start looking for it.

There's a widely accepted idea, of which Tim Robbins in

Bull Durham is the gutter version, that unconsummated eros is fuel for achievement. (I imagine that taking a vow of chastity is like having this thrillingly difficult attraction not for one person but for the whole universe.) The problem with the popular understanding of this equation is that it assumes that

frustration is doing most of the work. Assert that pedagogic eros is chaste without being frustrated and the popular understanding takes a nosedive. That's unfortunate, because the difference between pedagogic eros and sexual frustration is an important one. That, to bring a long post in for a landing, is why straights have a claim on the

Symposium in a post-coeducational world. The kind of eros that Socrates and Deresiewicz describe flourishes in relationships where the lower sort of eros isn't just absent but

implicitly and categorically off-limits, and, in our country and age, male professor/chick student fits the bill better than either gay male professor/gay male student (erotically charged but not so taboo) or straight male professor/straight male student (not erotically charged*).

This reversal of the Platonic idea is only funny because it takes the most celebrated and least controversial form of homoerotic love and hands it to the other team. I hope I've made half-clear (read that footnote again) that coeducation and the rest of the sexual liberation package deal made this switch inevitable. And

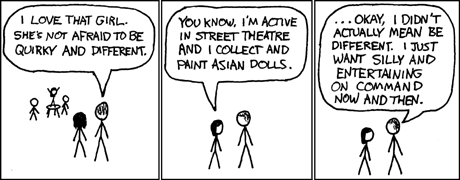

that's how we read Plato in Park Slope.

*Due in part to the presence of women. Straight men in all-male environments behave in a very particular spirit that evaporates when women show up.