Smoking is a practice in which a substance, most commonly tobacco or cannabis, is burned and the smoke is tasted or inhaled. This is primarily practised as a route of administration for recreational drug use, as combustion releases the active substances in drugs such as nicotine and makes them available for absorption through the lungs. It can also be done as a part of rituals, to induce trances and spiritual enlightenment.

The most common method of smoking today is through cigarettes, primarily industrially manufactured but also hand-rolled from loose tobacco and rolling paper. Other smoking implements include pipes, cigars, bidis, hookahs, vaporizers and bongs. It has been suggested that smoking-related disease kills one half of all long term smokers but these diseases may also be contracted by non-smokers. A 2007 report states that about 4.9 million people worldwide each year die as a result of smoking.

Smoking is one of the most common forms of recreational drug use. Tobacco smoking is today by far the most popular form of smoking and is practiced by over one billion people in the majority of all human societies. Less common drugs for smoking include cannabis and opium. Some of the substances are classified as hard narcotics, like heroin, but the use of these is very limited as they are often not commercially available.

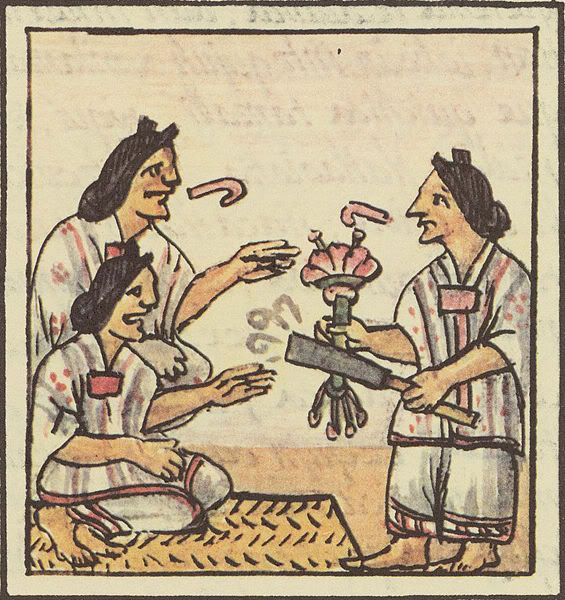

The history of smoking can be dated to as early as 5000 BC, and has been recorded in many different cultures across the world. Early smoking evolved in association with religious ceremonies; as offerings to deities, in cleansing rituals or to allow shamans and priests to alter their minds for purposes of divination or spiritual enlightenment. After the European exploration and conquest of the Americas, the practice of smoking tobacco quickly spread to the rest of the world. In regions like India and Subsaharan Africa, it merged with existing practices of smoking (mostly of cannabis). In Europe, it introduced a new type of social activity and a form of drug intake which previously had been unknown.

Perception surrounding smoking has varied over time and from one place to another; holy and sinful, sophisticated and vulgar, a panacea and deadly health hazard. Only relatively recently, and primarily in industrialized Western countries, has smoking come to be viewed in a decidedly negative light. Today medical studies have proven that smoking tobacco is among the leading causes of many diseases such as lung cancer, heart attacks, COPD, erectile dysfunction and can also lead to birth defects. The inherent health hazards of smoking have caused many countries to institute high taxes on tobacco products and anti-smoking campaigns are launched every year in an attempt to curb tobacco smoking.

The history of smoking dates back to as early as 5000 BC in shamanistic rituals. Many ancient civilizations, such as the Babylonians, Indians and Chinese, burnt incense as a part of religious rituals, as did the Israelites and the later Catholic and Orthodox Christian churches. Smoking in the Americas probably had its origins in the incense-burning ceremonies of shamans but was later adopted for pleasure, or as a social tool. The smoking of tobacco, as well as various hallucinogenic drugs was used to achieve trances and to come into contact with the spirit world.

Substances such as Cannabis, clarified butter (ghee), fish offal, dried snake skins and various pastes molded around incense sticks dates back at least 2000 years. Fumigation (dhupa) and fire offerings (homa) are prescribed in the Ayurveda for medical purposes, and have been practiced for at least 3,000 years while smoking, dhumrapana (literally "drinking smoke"), has been practiced for at least 2,000 years. Before modern times these substances have been consumed through pipes, with stems of various lengths or chillums.

Cannabis smoking was common in the Middle East before the arrival of tobacco, and was early on a common social activity that centered around the type of water pipe called a hookah. Smoking, especially after the introduction of tobacco, was an essential component of Muslim society and culture and became integrated with important traditions such as weddings, funerals and was expressed in architecture, clothing, literature and poetry.

Cannabis smoking was introduced to Sub-Saharan Africa through Ethiopia and the east African coast by either Indian or Arab traders in the 13th century or earlier and spread on the same trade routes as those that carried coffee, which originated in the highlands of Ethiopia. It was smoked in calabash water pipes with terra cotta smoking bowls, apparently an Ethiopian invention which was later conveyed to eastern, southern and central Africa.

At the time of the arrivals of Reports from the first European explorers and conquistadors to reach the Americas tell of rituals where native priests smoked themselves into such high degrees of intoxication that it is unlikely that the rituals were limited to just tobacco.

n 1612, six years after the settlement of Jamestown, John Rolfe was credited as the first settler to successfully raise tobacco as a cash crop. The demand quickly grew as tobacco, referred to as "golden weed", reviving the Virginia join stock company from its failed gold expeditions. In order to meet demands from the old world, tobacco was grown in succession, quickly depleting the land. This became a motivator to settle west into the unknown continent, and likewise an expansion of tobacco production. Indentured servitude became the primary labor force up until Bacon's Rebellion, from which the focus turned to slavery. This trend abated following the American revolution as slavery became regarded as unprofitable. However the practice was revived in 1794 with the invention of the cotton gin.

A Frenchman named Jean Nicot (from whose name the word nicotine is derived) introduced tobacco to France in 1560. From France tobacco spread to England. The first report of a smoking Englishman is of a sailor in Bristol in 1556, seen "emitting smoke from his nostrils". Like tea, coffee and opium, tobacco was just one of many intoxicants that was originally used as a form of medicine. Tobacco was introduced around 1600 by French merchants in what today is modern-day Gambia and Senegal. At the same time caravans from Morocco brought tobacco to the areas around Timbuktu and the Portuguese brought the commodity (and the plant) to southern Africa, establishing the popularity of tobacco throughout all of Africa by the 1650s.

Soon after its introduction to the Old World, tobacco came under frequent criticism from state and religious leaders. Murad IV, sultan of the Ottoman Empire 1623-40 was among the first to attempt a smoking ban by claiming it was a threat to public moral and health. The Chinese emperor Chongzhen issued an edict banning smoking two years before his death and the overthrow of the Ming dynasty. Later, the Manchu of the Qing dynasty, who were originally a tribe of nomadic horse warriors, would proclaim smoking "a more heinous crime than that even of neglecting archery". In Edo period Japan, some of the earliest tobacco plantations were scorned by the shogunate as being a threat to the military economy by letting valuable farmland go to waste for the use of a recreational drug instead of being used to plant food crops.

Religious leaders have often been prominent among those who considered smoking immoral or outright blasphemous. In 1634 the Patriarch of Moscow forbade the sale of tobacco and sentenced men and women who flouted the ban to have their nostrils slit and their backs whipped until skin came off their backs. The Western church leader Urban VII likewise condemned smoking in a papal bull of 1590. Despite many concerted efforts, restrictions and bans were almost universally ignored. When James I of England, a staunch anti-smoker and the author of a A Counterblaste to Tobacco, tried to curb the new trend by enforcing a whopping 4000% tax increase on tobacco in 1604, it proved a failure, as London had some 7,000 tobacco sellers by the early 17th century. Later, scrupulous rulers would realise the futility of smoking bans and instead turned tobacco trade and cultivation into lucrative government monopolies.

By the mid-17th century every major civilization had been introduced to tobacco smoking and in many cases had already assimilated it into the native culture, despite the attempts of many rulers to stamp the practice out with harsh penalties or fines. Tobacco, both product and plant, followed the major trade routes to major ports and markets, and then on into the hinterlands. The English language term smoking was coined in the late 18th century, before then the practice was referred to as drinking smoke.

Tobacco and cannabis were used in Sub-Saharan Africa, much like elsewhere in the world, to confirm social relations, but also created entirely new ones. In what is today Congo, a society called Bena Diemba ("People of Cannabis") was organized in the late 19th century in Lubuko ("The Land of Friendship"). The Bena Diemba were collectivist pacifists that rejected alcohol and herbal medicines in favor of cannabis.

The growth remained stable until the American Civil War in 1860s, from which the primary labor force transition from slavery to share cropping. This compounded with a change in demand, lead to the industrialization of tobacco production with the cigarette. James Bonsack, a craftsman, in 1881 produce a machine to speed the production in cigarettes.

In the 19th century the practice of smoking opium became common. Previously it had only been eaten, and then primarily for its medical properties. A massive increase in opium smoking in China was more or less directly instigated by the British trade deficit with Qing dynasty China. As a way to amend this problem, the British began exporting large amounts of opium grown in the Indian colonies. The social problems and the large net loss of currency led to several Chinese attempts to stop the imports which eventually culminated in the Opium Wars.

Opium smoking later spread with Chinese immigrants and spawned many infamous opium dens in China towns around South and Southeast Asia and Europe. In the latter half of the 19th century, opium smoking became popular in the artistic community in Europe, especially Paris; artists' neighborhoods such as Montparnasse and Montmartre became virtual "opium capitals". While opium dens that catered primarily to emigrant Chinese continued to exist in China Towns around the world, the trend among the European artists largely abated after the outbreak of World War I. The consumption of Opium abated in China during the Cultural revolution in the 1960s and 1970s.

With the modernization of cigarette production compounded with the increased life expectancies during the 1920s, adverse health effects began to become more prevalent. In Germany, anti-smoking groups, often associated with anti-liquor groups, first published advocacy against the consumption of tobacco in the journal Der Tabakgegner (The Tobacco Opponent) in 1912 and 1932. In 1929, Fritz Lickint of Dresden, Germany, published a paper containing formal statistical evidence of a lung cancer–tobacco link. During the Great depression Adolf Hitler condemned his earlier smoking habit as a waste of money, and later with stronger assertions. This movement was further strengthened with Nazi reproductive policy as women who smoked were viewed as unsuitable to be wives and mothers in a German family.

The movement in Nazi Germany did reach across enemy lines during the Second World War, as anti-smoking groups quickly lost popular support. By the end of the Second World War, American cigarette manufactures quickly reentered the German black market. Illegal smuggling of tobacco became prevalent, and leaders of the Nazi anti-smoking campaign were assassinated. As part of the Marshall Plan, the United States shipped free tobacco to Germany; with 24,000 tons in 1948 and 69,000 tons in 1949. Per capita yearly cigarette consumption in post-war Germany steadily rose from 460 in 1950 to 1,523 in 1963. By the end of the 20th century, anti-smoking campaigns in Germany were unable to exceed the effectiveness of the Nazi-era climax in the years 1939–41 and German tobacco health research was described by Robert N. Proctor as "muted".

Richard Doll in 1950 published research in the British Medical Journal showing a close link between smoking and lung cancer. Four years later, in 1954 the British Doctors Study, a study of some 40 thousand doctors over 20 years, confirmed the suggestion, based on which the government issued advice that smoking and lung cancer rates were related. In 1964 the United States Surgeon General's Report on Smoking and Health likewise began suggesting the relationship between smoking and cancer, which confirmed its suggestions 20 years later in the 1980s.

As scientific evidence mounted in the 1980s, tobacco companies claimed contributory negligence as the adverse health effects were previously unknown or lacked substantial credibility. Health authorities sided with these claims up until 1998, from which they reversed their position. The Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, originally between the four largest US tobacco companies and the Attorneys General of 46 states, restricted certain types of tobacco advertisement and required payments for health compensation; which later amounted to the largest civil settlement in United States history.

From 1965 to 2006, rates of smoking in the United States have declined from 42% to 20.8%. A significant majority of those who quit were professional, affluent men. Despite this decrease in the prevalence of consumption, the average number of

cigarettes consumed per person per day increased from 22 in 1954 to 30 in 1978. This paradoxical event suggests that those who quit smoked less, while those who continued to smoke moved to smoke more light cigarettes. This trend has been paralleled by many industrialized nations as rates have either leveled-off or declined. In the developing world, however, tobacco consumption continues to rise at 3.4% in 2002. In Africa, smoking is in most areas considered to be modern, and many of the strong adverse opinions that prevail in the West receive much less attention. Today Russia leads as the top consumer of tobacco followed by Indonesia, Laos, Ukraine, Belarus, Greece, Jordan, and China. The World Health Organization has begun a program known as the Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI) in order to reduce rates of consumption in the developing world.

In the early 1980s, organized international drug trafficking grew. However, compounded with overproduction and tighter legal enforcement for the illegal product, drug dealers decided to convert the powder to "crack" - a solid, smoke-able form of cocaine, that could be sold in smaller quantities, to more people. This trend abated in the 1990s as increased police action coupled with a robust economy deterred many potential candidates to forfeit or fail to take up the habit.

Recent years shows an increase in the consumption of vaporized heroin, methamphetamine and Phencyclidine (PCP). Along with a smaller number of psychedelic drugs such as DMT, 5-Meo-DMT, and Salvia divinorum

The most popular type of substance that is smoked is tobacco. There are many different tobacco cultivars which are made into a wide variety of mixtures and brands. Tobacco is often sold flavored, often with various fruit aromas, something which is especially popular for use with water pipes, such as hookahs. The second most common substance that is smoked is cannabis, made from the flowers or leaves of Cannabis sativa. The substance is considered illegal in most countries in the world and in those countries that tolerate public consumption, it is usually only pseudo-legal. Despite this, a considerable percentage of the adult population in many countries have tried it with smaller minorities doing it on a regular basis. Since cannabis is illegal or only tolerated in most jurisdictions, there is no industrial mass-production of cigarettes, meaning that the most common form of smoking is with hand-rolled

cigarettes (often called joints) or with pipes. Water pipes are also fairly common, and when used for cannabis are called bongs.

A few other recreational drugs are smoked by smaller minorities. Most of these substances are controlled, and some are considerably more intoxicating than either tobacco or cannabis. These include crack cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine and PCP. A small number of psychedelic drugs are also smoked, including DMT, 5-Meo-DMT, and Salvia divinorum.

An elaborately decorated pipe.

Even the most primitive form of smoking requires tools of some sort to perform. This has resulted in a staggering variety of smoking tools and paraphernalia from all over the world. Whether tobacco, cannabis, opium or herbs, some form of receptacle is required along with a source of fire to light the mixture. The most common today is by far the cigarette, consisting of a tightly rolled tube of paper, which is usually manufactured industrially or rolled from loose tobacco, rolling papers which can include a filter. Other popular smoking tools are various pipes and cigars. A less common but increasingly popular form is through vaporizers, which operate using hot air convection by heating and delivering the substance without combustion; thereby decreasing health risks to the lungs.

Other than the actual smoking equipment, many other items are associated with smoking; cigarette cases, cigar boxes, lighters, matchboxes, cigarette holders, cigar holders, ashtrays, pipe cleaners, tobacco cutters, match stands, pipe tampers, cigarette companions and so on. Many of these have become valuable collector items and particularly ornate and antique items can fetch high prices at the finest auction houses.

An allegedly healthier alternative to smoking appeared in 2004 with the introduction of electronic cigarettes. These battery-operated, cigarette-like devices produce an aerosol intended to mimic the smoke from burning tobacco, delivering nicotine to the user without many of the other harmful substances released in tobacco smoke. Claims that electronic

cigarettes are overall less harmful to use than real cigarettes are, however, disputed, as is their legal status in many countries.

Tobacco-related diseases are some of the biggest killers in the world today and are cited as one of the biggest causes of premature death in industrialized countries. In the United States about 500,000 deaths per year are attributed to smoking-related diseases and a recent study estimated that as much as 1/3 of China's male population will have significantly shortened life-spans due to smoking. Male and female smokers lose an average of 13.2 and 14.5 years of life, respectively. At least half of all lifelong smokers die earlier as a result of smoking.The risk of dying from lung cancer before age 85 is 22.1% for a male smoker and 11.9% for a female current smoker, in the absence of competing causes of death. The corresponding estimates for lifelong nonsmokers are a 1.1% probability of dying from lung cancer before age 85 for a man of European descent, and a 0.8% probability for a woman. Smoking one cigarette a day results in a risk of heart disease that is halfway between that of a smoker and a non-smoker. The non-linear dose response relationship is explained by smoking's effect on platelet aggregation.

Among the diseases that can be caused by smoking are vascular stenosis, lung cancer, heart attacks and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

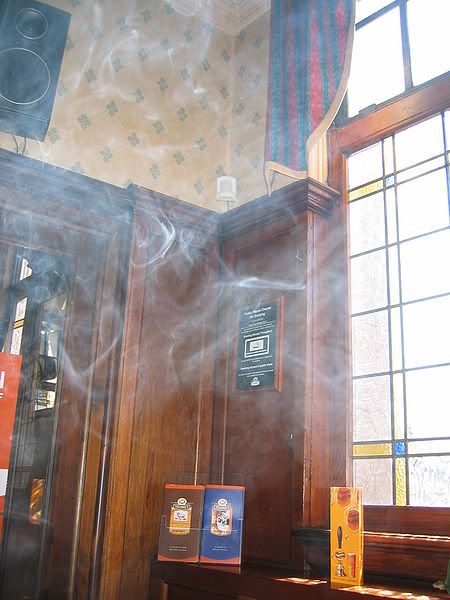

Many governments are trying to deter people from smoking with anti-smoking campaigns in mass media stressing the harmful long-term effects of smoking. Passive smoking, or secondhand smoking, which affects people in the immediate vicinity of smokers, is a major reason for the enforcement of smoking bans. This is a law enforced to stop individuals smoking in indoor public places, such as bars, pubs and restaurants. The idea behind this is to discourage smoking by making it more inconvenient, and to stop harmful smoke being present in enclosed public spaces. A common concern among legislators is to discourage smoking among minors and many states have passed laws against selling tobacco products to underage customers. Many developing countries have not adopted anti-smoking policies, leading some to call for anti-smoking campaigns and further education to explain the negative effects of ETS (Environmental Tobacco Smoke) in developing countries.[citation needed]

Despite the many bans, European countries still hold 18 of the top 20 spots, and according to the ERC, a market research company, the heaviest smokers are from Greece, averaging 3,000 cigarettes per person in 2007. Rates of smoking have leveled off or declined in the developed world but continue to rise in developing countries. Smoking rates in the United States have dropped by half from 1965 to 2006, falling from 42% to 20.8% in adults.

The effects of addiction on society vary considerably between different substances that can be smoked and the indirect social problems that they cause, in great part because of the differences in legislation and the enforcement of narcotics legislation around the world. Though nicotine is a highly addictive drug, its effects on cognition are not as intense or noticeable as other drugs such as, cocaine, amphetamines or any of the opiates (including heroin and morphine).[citation needed]

Smoking is a risk factor in Alzheimer's Disease. While smoking more than 15 cigarettes per day has been shown to worsen the symptoms of Crohn's Disease, smoking has been shown to actually lower the prevalence of ulcerative colitis.

Inhaling the vaporized gas form of substances into the lungs is a quick and very effective way of delivering drugs into the bloodstream (as the gas diffuses directly into the pulmonary vein, then into the heart and from there to the brain) and affects the user within less than a second of the first inhalation. The lungs consist of several million tiny bulbs called alveoli that altogether have an area of over 70 m² (about the area of a tennis court). This can be used to administer useful medical as well as recreational drugs such as aerosols, consisting of tiny droplets of a medication, or as gas produced by burning plant material with a psychoactive substance or pure forms of the substance itself. Not all drugs can be smoked, for example the sulphate derivative that is most commonly inhaled through the nose, though purer free base forms of substances can, but often require considerable skill in administering the drug properly. The method is also somewhat inefficient since not all of the smoke will be inhaled. The inhaled substances trigger chemical reactions in nerve endings in the brain due to being similar to naturally occurring substances such as endorphins and dopamines, which are associated with sensations of pleasure. The result is what is usually referred to as a "high" that ranges between the mild stimulus caused by nicotine to the intense euphoria caused by heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines.

Inhaling smoke into the lungs, no matter the substance, has adverse effects on one's health. The incomplete combustion produced by burning plant material, like tobacco or cannabis, produces carbon monoxide, which impairs the ability of blood to carry oxygen when inhaled into the lungs. There are several other toxic compounds in tobacco that constitute serious health hazards to long-term smokers from a whole range of causes; vascular abnormalities such as stenosis, lung cancer, heart attacks, strokes, impotence, low birth weight of infants born by smoking mothers. 8% of long-term smokers develop the characteristic set of facial changes known to doctors as smoker's face.

Most tobacco smokers begin during adolescence or early adulthood. Smoking has elements of risk-taking and rebellion, which often appeal to young people. The presence of high-status models and peers may also encourage smoking. Because teenagers are influenced more by their peers than by adults, attempts by parents, schools, and health professionals at preventing people from trying

cigarettes are often unsuccessful.

Smokers often report that cigarettes help relieve feelings of stress. However, the stress levels of adult smokers are slightly higher than those of nonsmokers, adolescent smokers report increasing levels of stress as they develop regular patterns of smoking, and smoking cessation leads to reduced stress. Far from acting as an aid for mood control, nicotine dependency seems to exacerbate stress. This is confirmed in the daily mood patterns described by smokers, with normal moods during smoking and worsening moods between cigarettes. Thus, the apparent relaxant effect of smoking only reflects the reversal of the tension and irritability that develop during nicotine depletion. Dependent smokers need nicotine to remain feeling normal.

Psychologists such as Hans Eysenck have developed a personality profile for the typical smoker. Extraversion is the trait that is most associated with smoking, and smokers tend to be sociable, impulsive, risk taking, and excitement-seeking individuals. Although personality and social factors may make people likely to smoke, the actual habit is a function of operant conditioning. During the early stages, smoking provides pleasurable sensations (because of its action on the dopamine system) and thus serves as a source of positive reinforcement. After an individual has smoked for many years, the avoidance of withdrawal symptoms and negative reinforcement become the key motivations. Although smoking tobacco has long been seen as a universally addictive trait, it has been proven statistically that people take a varying amount of time to become dependent on the drug nicotine. In fact, the graph showing percentage of the "population showing addictive behaviour" vs "amount of nicotine taken" levels off before reaching 100% of the population, showing that a proportion of people never become dependent on nicotine at all.

However, because people who smoke are engaging in an activity that has negative effects on health, they tend to rationalize their behavior. In other words, they develop convincing, if not necessarily logical, reasons why smoking is acceptable for them to do. For example, a smoker could justify his or her behavior by concluding that everyone dies and so cigarettes do not actually change anything. Or a person could believe that smoking relieves stress or has other benefits that justify its risks. Smokers who need a cigarette first thing in the morning will often quote the positive effects, but will not accept that they awake feeling below normal levels of happiness (lower levels of dopamine) and merely smoke to return themselves to a "normal" level of happiness ("normal" level of dopamine).

Smoking, primarily of tobacco, is an activity that is practiced by some 1.1 billion people, and up to 1/3 of the adult population. The image of the smoker can vary considerably, but is very often associated, especially in fiction, with individuality and aloofness. Even so, smoking of both tobacco and cannabis can be a social activity which serves as a reinforcement of social structures and is part of the cultural rituals of many and diverse social and ethnic groups. Many smokers begin smoking in social settings and the offering and sharing of a cigarette is often an important rite of initiation or simply a good excuse to start a conversation with strangers in many settings; in bars, night clubs, at work or on the street. Lighting a cigarette is often seen as an effective way of avoiding the appearance of idleness or mere loitering. For adolescents, it can function as a first step out of childhood or as an act of rebellion against the adult world. Also, smoking can be seen as a sort of camaraderie. It has been shown that even opening a packet of cigarettes, or offering a cigarette to other people, can increase the level of dopamine (the "happy feeling") in the brain, and it is doubtless that people who smoke form relationships with fellow smokers, in a way that only proliferates the habit, particularly in countries where smoking inside public places has been made illegal. Other than recreational drug use, it can be used to construct identity and a development of self-image by associating it with personal experiences connected with smoking. The rise of the modern anti-smoking movement in the late 19th century did more than create awareness of the hazards of smoking; it provoked reactions of smokers against what was, and often still is, perceived as an assault on personal freedom and has created an identity among smokers as rebels or outcasts, apart from non-smokers:

"There is a new Marlboro land, not of lonesome cowboys, but of social-spirited urbanites, united against the perceived strictures of public health."The importance of tobacco to soldiers was early on recognized as something that could not be ignored by commanders. By the 17th century allowances of tobacco were a standard part of the naval rations of many nations and by World War I cigarette manufacturers and governments collaborated in securing tobacco and cigarette allowances to soldiers in the field. It was asserted that regular use of tobacco while under duress would not only calm the soldiers, but allow them to withstand greater hardship. Until the mid-20th century, the majority of the adult population in many Western nations were smokers and the claims of anti-smoking activists were met with much skepticism, if not outright contempt. Today the movement has considerably more weight and evidence of its claims, but a considerable proportion of the population remains steadfast smokers.

Smoking has been accepted into culture, in various art forms, and has developed many distinct, and often conflicting or mutually exclusive, meanings depending on time, place and the practitioners of smoking. Pipe smoking, until recently one of the most common forms of smoking, is today often associated with solemn contemplation, old age and is often considered quaint and archaic. Cigarette smoking, which did not begin to become widespread until the late 19th century, has more associations of modernity and the faster pace of the industrialized world. Cigars have been, and still are, associated with masculinity, power and is an iconic image associated with the stereotypical capitalist. Smoking in public has for a long time been something reserved for men and when done by women has been associated with promiscuity. In Japan during the Edo period, prostitutes and their clients would often approach one another under the guise of offering a smoke and the same was true for 19th century Europe.

The earliest depictions of smoking can be found on Classical Mayan pottery from around the 9th century. The art was primarily religious in nature and depicted deities or rulers smoking early forms of cigarettes.Soon after smoking was introduced outside of the Americas it began appearing in painting in Europe and Asia. The painters of the Dutch Golden Age were among the first to paint portraits of people smoking and still lifes of pipes and tobacco. For southern European painters of the 17th century, a pipe was much too modern to include in the preferred motifs inspired by mythology from Greek and Roman antiquity. At first smoking was considered lowly and was associated with peasants. Many early paintings were of scenes set in taverns or brothels. Later, as the Dutch Republic rose to considerable power and wealth, smoking became more common amongst the affluent and portraits of elegant gentlemen tastefully raising a pipe appeared. Smoking represented pleasure, transience and the briefness of earthly life as it, quite literally, went up in smoke. Smoking was also associated with representations of both the sense of smell and that of taste.

In the 18th century smoking became far more sparse in painting as the elegant practice of taking snuff became popular. Smoking a pipe was again relegated to portraits of lowly commoners and country folk and the refined sniffing of shredded tobacco followed by sneezing was rare in art. When smoking appeared it was often in the exotic portraits influenced by Orientalism. Many proponents of post-colonial theory controversially believe this portrayal was a means of projecting an image of European superiority over its colonies and a perception of the male dominance of a feminized Orient. They believe the theme of the exotic and alien "Other" escalated in the 19th century, fueled by the rise in popularity of ethnology during the Enlightenment.

In the 19th century smoking was common as a symbol of simple pleasures; the pipe smoking "noble savage", solemn contemplation by Classical Roman ruins, scenes of an artists becoming one with nature while slowly toking a pipe. The newly empowered middle class also found a new dimension of smoking as a harmless pleasure enjoyed in smoking saloons and libraries. Smoking a cigarette or a cigar would also become associated with the bohemian, someone who shunned the conservative middle class values and displayed his contempts for conservatism. But this was a pleasure that was to be confined to a male world; women smokers were associated with prostitution and was not considered an activity in which proper ladies should involve themselves. It was not until the turn of the century that smoking women would appear in paintings and photos, giving a chic and charming impression. Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, who was a pipe smoker himself, would also begin to associate smoking with gloom and fin-du-siècle fatalism.

While the symbolism of the cigarette, pipe and cigar respectively were consolidated in the late 19th century, it was not until the 20th century that artists began to use it fully; a pipe would stand for thoughtfulness and calm; the cigarette symbolized modernity, strength and youth, but also nervous anxiety; the cigar was a sign of authority, wealth and power. The decades following World War II, during the apex of smoking when the practice had still not come under fire by the growing anti-smoking movement, a cigarette casually tucked between the lips represented the young rebel, epitomized in actors like Marlon Brando and James Dean or mainstays of advertising like the Marlboro Man. It was not until the 1970s when the negative aspects of smoking began to appear; the unhealthy lower-class loser, reeking of cigarette smoke and lack of motivation and drive, especially in art inspired or commissioned by anti-smoking campaigns.

Ever since the era of silent films, smoking has had a major part in film symbolism. In the hard boiled film noir crime thrillers, cigarette smoke often frames characters and is frequently used to add an aura of mystique or even nihilism. One of the forerunners of this symbolism can be seen in Fritz Lang's Weimar era Dr Mabuse, der Spieler, 1922 (Dr Mabuse, the Gambler), where men mesmerized by card playing smoke cigarettes while gambling.

Female smokers in film were also early on associated with a type of sensuous and seductive sexuality, most notably personified by German film star Marlene Dietrich. Similarly, actors like Humphrey Bogart and Audrey Hepburn have been closely identified with their smoker persona, and some of their most famous portraits and roles have involved them being haloed by a mist of cigarette smoke. Hepburn often enhanced the glamour with a cigarette holder, most notably in the film Breakfast at Tiffany's. Smoking could also be used as a means to subvert censorship, as two cigarettes burning unattended in an ashtray was often used to 'suggest' sexual activity.

Since World War II, smoking has gradually become less frequent on screen as the obvious health hazards of smoking have become more widely known. With the anti-smoking movement gaining greater respect and influence, conscious attempts not to show smoking on screen are now undertaken in order to avoid encouraging smoking or giving it positive associations, particularly for family films. Smoking on screen is more common today among characters who are portrayed as anti-social or even criminal.[

Just as in other types of fiction, smoking has had an important place in literature and smokers are often portrayed as characters with great individuality, or outright eccentrics, something typically personified in one of the most iconic smoking literary figures of all, Sherlock Holmes. Other than being a frequent part of short stories and novels, smoking has spawned endless eulogies, praising its qualities and affirming the author's identity as a devoted smoker. Especially during the late 19th century and early 20th century, a panoply of books with titles like Tobacco: Its History and associations (1876), Cigarettes in Fact and Fancy (1906) and Pipe and Pouch: The Smokers Own Book of Poetry (1905) were written in the UK and the US. The titles were written by men for other men and contained general tidbits and poetic musings about the love for tobacco and all things related to it, and frequently praised the refined bachelor's life. The Fragrant Weed: Some of the Good Things Which Have been Said or Sung about Tobacco, published in 1907, contained, among many others, the following lines from the poem A Bachelor's Views by Tom Hall that were typical of the attitude in many of the books:

"So let us drink

To her, – but think

Of him who has to keep her;

And sans a wife

Let's spend our life

In bachelordom, – it's cheaper. ”

—Eugene Umberger"These works were all published in an era before the cigarette had become the dominant form of tobacco consumption and pipes, cigars and chewing tobacco were still commonplace. Many of the books were published in novel packaging that would attract the learned smoking gentleman. Pipe and Pouch came in a leather bag resembling a tobacco pouch and Cigarettes in Fact and Fancy (1901) came bound in leather, packaged in an imitation cardboard cigar box. By the late 1920s, the publication of this type of literature largely abated and was only sporadically revived in the later 20th century.

here have been few examples of tobacco in music in early modern times, though there are occasional signs of influence in pieces such as Johann Sebastian Bach's Edifying Thoughts of a Tobacco-Smoker. However, from the early 20th century and onwards smoking has been closely associated with popular music. Jazz was from early on closely intertwined with the smoking that was practiced in the venues where it was played, such as bars, dance halls, jazz clubs and even brothels. The rise of jazz coincided with the expansion of the modern tobacco industry, and in the United States also contributed to the spread of cannabis. The latter went under names like "tea", "muggles" and "reefer" in the jazz community and was so influential in the 1920s and 30s that it found its way into songs composed at the time such as Louis Armstrong's Muggles Larry Adler's Smoking Reefers and Don Redman's Chant of The Weed. The popularity of marijuana among jazz musicians remained high until the 1940s and 50s, when it was partially replaced by the use of heroin.

Another form of modern popular music that has been closely associated with cannabis smoking is reggae, a style of music that originated in Jamaica in the late 1950s and early 60s. Cannabis, or ganja, is believed to have been introduced to Jamaica in the mid-19th century by Indian immigrant labor and was primarily associated with Indian workers until it was appropriated by the Rastafari movement in the middle of the 20th century. The Rastafari considered cannabis smoking to be a way to come closer to God, or Jah, an association that was greatly popularized by reggae icons such as Bob Marley and Peter Tosh in the 1960s and 70s.

Estimates claim that smokers cost the U.S. economy $97.6 billion a year in lost productivity, and that an additional $96.7 billion is spent on public and private health care combined. This is over 1% of the gross domestic product. A male smoker in the United States that smokes more than one pack a day can expect an average increase of $19,000 just in medical expenses over the course of his lifetime. A U.S. female smoker that also smokes more than a pack a day can expect an average of $25,800 additional healthcare costs over her lifetime. These costs must be offset against the extra tax revenue that smoking provides.