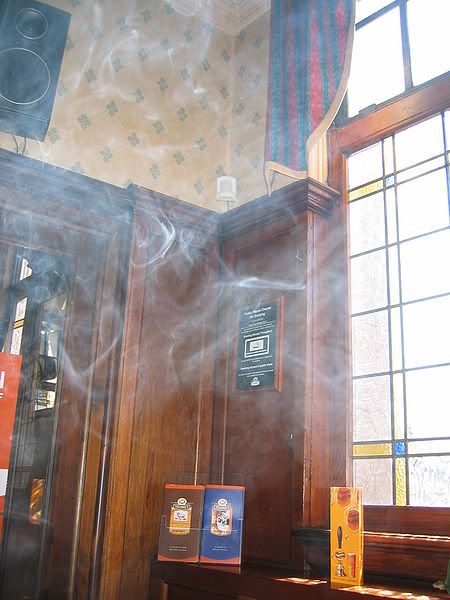

Passive smoking is the inhalation of smoke, called secondhand smoke (SHS) or environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), from tobacco products used by others. It occurs when tobacco smoke permeates any environment, causing its inhalation by people within that environment. Scientific evidence shows that exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke causes disease, disability, and death.

Passive smoking has played a central role in the debate over the harms and regulation of tobacco products. Since the early 1970s, the tobacco industry has been concerned about passive smoking as a serious threat to its business interests; harm to bystanders was perceived as a motivator for stricter regulation of tobacco products. Despite the awareness of results "strongly suggestive" of harms from secondhand smoke as early as the 1980s, the tobacco industry coordinated a scientific controversy with the aim of forestalling regulation of their products.:1242 Currently, the health risks of secondhand smoke are a matter of scientific consensus, and these risks have been one of the major motivations for smoking bans in workplaces and indoor public places, including restaurants, bars and night clubs.

Secondhand smoke causes many of the same diseases as direct smoking, including cardiovascular diseases, lung cancer, and respiratory diseases. These diseases include:

* Cancer:

o General: overall increased risk; reviewing the evidence accumulated on a worldwide basis, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded in 2004 that "Involuntary smoking (exposure to secondhand or 'environmental' tobacco smoke) is carcinogenic to humans."

o Lung cancer: the effect of passive smoking on lung cancer has been extensively studied. A series of studies from the USA from 1986–2003, the UK in 1998, Australia in 1997 and internationally in 2004 have consistently shown a significant increase in relative risk among those exposed to passive smoke.

o Breast cancer: The California Environmental Protection Agency concluded in 2005 that passive smoking increases the risk of breast cancer in younger, primarily premenopausal women by 70% and the US Surgeon General has concluded that the evidence is "suggestive," but still insufficient to assert such a causal relationship. In contrast, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded in 2004 that there was "no support for a causal relation between involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke and breast cancer in never-smokers."

o Renal cell carcinoma (RCC): A recent study shows an increased RCC risk among never smokers with combined home/work exposure to passive smoking.

o Passive smoking does not appear to be associated with pancreatic cancer.

o Brain tumor: The risk in children increases significantly with higher amount of passive smoking, even if the mother doesn't smoke, thus not restricting risk to prenatal exposure during pregnancy.

* Ear, nose, and throat: risk of ear infections.

o Secondhand smoke exposure is associated with hearing loss in non-smoking adults.

* Circulatory system: risk of heart disease, reduced heart rate variability, higher heart rate.

o Epidemiological studies have shown that both active and passive cigarette smoking increase the risk of atherosclerosis.

* Lung problems:

o Risk of asthma.

* Cognitive impairment and dementia: Exposure to secondhand smoke may increase the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in adults 50 and over.

* During pregnancy:

o Low birth weight, part B, ch. 3.

o Premature birth, part B, ch. 3 (Note that evidence of the causal link is only described as "suggestive" by the US Surgeon General in his 2006 report.)

o Recent studies comparing women exposed to Environmental Tobacco Smoke and non-exposed women, demonstrate that women exposed while pregnant have higher risks of delivering a child with congenital abnormalities, longer lengths, smaller head circumferences, and low birth weight.

* General:

o Worsening of asthma, allergies, and other conditions.

* Risk to children:]

o Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In his 2006 report, the US Surgeon General concludes: "The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between exposure to secondhand smoke and sudden infant death syndrome."

o Asthma

o Lung infections

o More severe illness with bronchiolitis, and worse outcome

o Increased risk of developing tuberculosis if exposed to a carrier

o Allergies

o Crohn's disease.

o Learning difficulties, developmental delays, and neurobehavioral effects. Animal models suggest a role for nicotine and carbon monoxide in neurocognitive problems.

o An increase in tooth decay (as well as related salivary biomarkers) has been associated with passive smoking in children.

o Increased risk of middle ear infections.

* Skin Disorder

o Childhood exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke is associated with an increased risk of the development of adult-onset Atopic dermatitis.

* Overall increased risk of death in both adults, where it is estimated to kill 53,000 nonsmokers per year, making it the 3rd leading cause of preventable death in the U.S. and in children. Another research financed by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and Bloomberg Philanthropies found that passive smoking causes about 603,000 death a year, which represents 1% of the world's death.

Epidemiological studies show that non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke are at risk for many of the health problems associated with direct smoking.

In 1992, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a review of available evidence on the relationship between secondhand smoke and heart disease, and estimated that passive smoking was responsible for 35,000 to 40,000 deaths per year in the United States in the early 1980s. The absolute risk increase of heart disease due to ETS was 2.2%, while the attributable risk percent was 23%.

Research using more exact measures of secondhand smoke exposure suggests that risks to nonsmokers may be even greater than this estimate. A British study reported that exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk of heart disease among non-smokers by as much as 60%, similar to light smoking. Evidence also shows that inhaled sidestream smoke, the main component of secondhand smoke, is about four times more toxic than mainstream smoke, a fact that known to the tobacco industry since the 1980s, which kept its findings secret. Some scientists believe that the risk of passive smoking, in particular the risk of developing coronary heart diseases, may have been substantially underestimated.

A minority of epidemiologists find it hard to understand how environmental tobacco smoke, which is far more dilute than actively inhaled smoke, could have an effect that is such a large fraction of the added risk of coronary heart disease among active smokers. One proposed explanation is that secondhand smoke is not simply a diluted version of "mainstream" smoke, but has a different composition with more toxic substances per gram of total particulate matter. Passive smoking appears to be capable of precipitating the acute manifestations of cardio-vascular diseases (atherothrombosis) and may also have a negative impact on the outcome of patients who suffer acute coronary syndromes.

In 2004, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO) reviewed all significant published evidence related to tobacco smoking and cancer. It concluded:

These meta-analyses show that there is a statistically significant and consistent association between lung cancer risk in spouses of smokers and exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke from the spouse who smokes. The excess risk is of the order of 20% for women and 30% for men and remains after controlling for some potential sources of bias and confounding.

Subsequent meta-analyses have confirmed these findings, and additional studies have found that high overall exposure to passive smoke even among people with non-smoking partners is associated with greater risks than partner smoking and is widespread in non-smokers.

The National Asthma Council of Australia cites studies showing that environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) is probably the most important indoor pollutant, especially around young children:

* Smoking by either parent, particularly by the mother, increases the risk of asthma in children.

* The outlook for early childhood asthma is less favourable in smoking households.

* Children with asthma who are exposed to smoking in the home generally have more severe disease.

* Many adults with asthma identify ETS as a trigger for their symptoms.

* Doctor-diagnosed asthma is more common among non-smoking adults exposed to ETS than those not exposed. Among people with asthma, higher ETS exposure is associated with a greater risk of severe attacks.

In France, passive smoking has been estimated to cause between 3,000 and 5,000 premature deaths per year, with the larger figure cited by Prime minister Dominique de Villepin during his announcement of a nationwide smoking ban: "That makes more than 13 deaths a day. It is an unacceptable reality in our country in terms of public health."

There is good observational evidence that smoke-free legislation reduces the number of hospital admissions for heart disease. In 2009 two studies in the United States confirmed the effectiveness of public smoking bans in preventing heart attacks. The first study, done at the University of California, San Francisco and funded by the National Cancer Institute, found a 15 percent decline in heart-attack hospitalizations in the first year after smoke-free legislation was passed, and 36 percent after three years. The second study, done at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, showed similar results. Overall, women, nonsmokers, and people under age 60 had the most heart attack risk reduction. Many of those benefiting were hospitality and entertainment industry workers.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization concluded in 2004 that there was sufficient evidence that secondhand smoke caused cancer in humans. Most experts believe that moderate, occasional exposure to secondhand smoke presents a small but measurable cancer risk to nonsmokers. The overall risk depends on the effective dose received over time. The risk level is higher if non-smokers spend many hours in an environment where cigarette smoke is widespread, such as a business where many employees or patrons are smoking throughout the day, or a residential care facility where residents smoke freely. The US Surgeon General, in his 2006 report, estimated that living or working in a place where smoking is permitted increases the non-smokers' risk of developing heart disease by 25–30% and lung cancer by 20–30%.

Environmental Tobacco Smoke can be evaluated either by directly measuring tobacco smoke pollutants found in the air or by using biomarkers, an indirect measure of exposure. As of 2005, Nicotine, cotinine, thiocyanates, and proteins are the most specific biological markers of tobacco smoke exposure.

* Cotinine

o Cotinine, the metabolite of Nicotine, is the preferred biomarker of Environmental Tobacco Smoke exposure. Typically, Cotinine is measured in the blood, saliva, and urine. Hair analysis has recently become a new, noninvasive measurement technique. Cotinine accumulates in hair during hair growth, which results in a measure of long-term, cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke.

o Urinary cotinine levels have been a reliable biomarker of tobacco exposure and have been used as a reference in many epidemiological studies. However, cotinine levels found in the urine only reflect exposure over the preceding 48 hours. Cotinine levels of the skin, such as the hair and nails, reflect tobacco exposure over the previous three months and are a more reliable biomarker.

o Cotinine is a much more reliable biomarker of Environmental Tobacco Smoke than surveys. Certain groups of people are reluctant to disclose their smoking status and exposure to tobacco smoke, especially pregnant women and parents of young children. This is due to their smoking being socially unacceptable. Also, recall of tobacco smoke exposure may be difficult. Cotinine measurements are therefore more reliable biomarkers.

In 2007, the Addictive Behaviors Journal found a positive correlation between secondhand tobacco smoke exposure and concentrations of nicotine and/or biomarkers of nicotine in the body. A significant amount of biological levels of nicotine from secondhand smoke exposure were equivalent to nicotine levels from active smoking and levels that are associated with behavior changes due to nicotine consumption.

A 2004 study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization concluded that nonsmokers are exposed to the same carcinogens as active smokers. Sidestream smoke contains more than 4,000 chemicals, including 69 known carcinogens. Of special concern are polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines, and aromatic amines, such as 4-Aminobiphenyl, all known to be highly carcinogenic. Mainstream smoke, sidestream smoke, and secondhand smoke contain largely the same components, however the concentration varies depending on type of smoke. Several well-established carcinogens have been shown by the tobacco companies' own research to be present at higher concentrations in sidestream smoke than in mainstream smoke.

Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) has been shown to produce more particulate-matter (PM) pollution than an idling low-emission diesel engine. In an experiment conducted by the Italian National Cancer Institute, three cigarettes were left smoldering, one after the other, in a 60 m³ garage with a limited air exchange. The cigarettes produced PM pollution exceeding outdoor limits, as well as PM concentrations up to 10-fold that of the idling engine.

Tobacco smoke exposure has immediate and substantial effects on blood and blood vessels in a way that increases the risk of a heart attack, particularly in people already at risk. Exposure to tobacco smoke for 30 minutes significantly reduces coronary flow velocity reserve in healthy nonsmokers.

Pulmonary emphysema can be induced in rats through acute exposure to sidestream tobacco smoke (30 cigarettes per day) over a period of 45 days. Degranulation of mast cells contributing to lung damage has also been observed.

The term "third-hand smoke" was recently coined to identify the residual tobacco smoke contamination that remains after the cigarette is extinguished and secondhand smoke has cleared from the air. Preliminary research suggests that byproducts of thirdhand smoke may pose a health risk, though the magnitude of risk, if any, remains unknown.

In 2008, there were more than 161,000 deaths attributed to lung cancer in the United States. Of these deaths, an estimated 10% to 15% were caused by factors other than first-hand smoking; equivalent to 16,000 to 24,000 deaths annually. Slightly more than half of the lung cancer deaths caused by factors other than first-hand smoking were found in nonsmokers. Lung cancer in nonsmokers may well be considered one of the most common cancer mortalities in the United States. Clinical epidemiology of lung cancer has linked the primary factors closely tied to lung cancer in nonsmokers as exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke, carcinogens including radon, and other indoor air pollutants.

Recent major surveys conducted by the U.S. National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control have found widespread public belief that secondhand smoke is harmful. In both 1992 and 2000 surveys, more than 80% of respondents agreed with the statement that secondhand smoke was harmful. A 2001 study found that 95% of adults agreed that secondhand smoke was harmful to children, and 96% considered tobacco-industry claims that secondhand smoke was not harmful to be untruthful.

A 2007 Gallup poll found that 56% of respondents felt that secondhand smoke was "very harmful", a number that has held relatively steady since 1997. Another 29% believe that secondhand smoke is "somewhat harmful"; 10% answered "not too harmful", while 5% said "not at all harmful".

As part of its attempt to prevent or delay tighter regulation of smoking, the tobacco industry funded a number of scientific studies and, where the results cast doubt on the risks associated with passive smoking, sought wide publicity for those results. The industry also funded libertarian and conservative think tanks, such as the Cato Institute in the United States and the Institute of Public Affairs in Australia which criticised both scientific research on passive smoking and policy proposals to restrict smoking. These industry-wide coordinated activities constitute one of the earliest expressions of corporate denialism. Today, not all criticism comes from the tobacco industry or its front groups: building up on the desinformation spread by the tobacco industry, a tobacco denialism movement has emerged, sharing many characteristics of other forms of denialism, such as HIV-AIDS denialism.

A 2003 study by Enstrom and Kabat, published in the British Medical Journal, argued that the harms of passive smoking had been overstated. Their analysis reported no statistically significant relationship between passive smoking and lung cancer, though the accompanying editorial noted that "they may overemphasise the negative nature of their findings."This paper was widely promoted by the tobacco industry as evidence that the harms of passive smoking were unproven. The American Cancer Society (ACS), whose database Enstrom and Kabat used to compile their data, criticized the paper as "neither reliable nor independent", stating that scientists at the ACS had repeatedly pointed out serious flaws in Enstrom and Kabat's methodology prior to publication. Notably, the study had failed to identify a comparison group of "unexposed" persons.

Enstrom's ties to the tobacco industry also drew scrutiny; in a 1997 letter to Philip Morris, Enstrom requested a "substantial research commitment... in order for me to effectively compete against the large mountain of epidemiologic data and opinions that already exist regarding the health effects of ETS and active smoking." In a US racketeering lawsuit against tobacco companies, the Enstrom and Kabat paper was cited by the US District Court as "a prime example of how nine tobacco companies engaged in criminal racketeering and fraud to hide the dangers of tobacco smoke." The Court found that the study had been funded and managed by the Center for Indoor Air Research, a tobacco industry front group tasked with "offsetting" damaging studies on passive smoking, as well as by Phillip Morris who stated that Ernstrom's work was "clearly litigation-oriented." Enstrom has defended the accuracy of his study against what he terms "illegitimate criticism by those who have attempted to suppress and discredit it."

A 1998 report by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) on environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) found "weak evidence of a dose-response relationship between risk of lung cancer and exposure to spousal and workplace ETS."

In March 1998, before the study was published, reports appeared in the media alleging that the IARC and the World Health Organization (WHO) were suppressing information. The reports, appearing in the British Sunday Telegraph and The Economist, among other sources, alleged that the WHO withheld from publication of its own report that supposedly failed to prove an association between passive smoking and a number of other diseases (lung cancer in particular).

In response, the WHO issued a press release stating that the results of the study had been "completely misrepresented" in the popular press and were in fact very much in line with similar studies demonstrating the harms of passive smoking.The study was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in October of the same year. An accompanying editorial summarized:

When all the evidence, including the important new data reported in this issue of the Journal, is assessed, the inescapable scientific conclusion is that ETS is a low-level lung carcinogen.

With the release of formerly classified tobacco industry documents through the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, it was found that the controversy over the WHO's alleged suppression of data had been engineered by Philip Morris, British American Tobacco, and other tobacco companies in an effort to discredit scientific findings which would harm their business interests. A WHO inquiry, conducted after the release of the tobacco-industry documents, found that this controversy was generated by the tobacco industry as part of its larger campaign to cut the WHO's budget, distort the results of scientific studies on passive smoking, and discredit the WHO as an institution. This campaign was carried out using a network of ostensibly independent front organizations and international and scientific experts with hidden financial ties to the industry.

The passive smoking issue poses a serious economic threat to the tobacco industry. It has broadened the definition of smoking beyond a personal habit to something with a social impact. In a confidential 1978 report, the tobacco industry described increasing public concerns about passive smoking as "the most dangerous development to the viability of the tobacco industry that has yet occurred." In United States of America v. Philip Morris et al., the District Court for the District of Columbia found that the tobacco industry "... recognized from the mid-1970s forward that the health effects of passive smoking posed a profound threat to industry viability and cigarette profits," and that the industry responded with "efforts to undermine and discredit the scientific consensus that ETS causes disease."

Accordingly, the tobacco industry have developed several strategies to minimize its impact on their business:

* The industry has sought to position the passive smoking debate as essentially concerned with civil liberties and smokers' rights rather than with health, by funding groups such as FOREST.

* Funding bias in research; in all reviews of the effects of passive smoking on health published between 1980 and 1995, the only factor associated with concluding that passive smoking is not harmful was whether an author was affiliated with the tobacco industry. However, not all studies that failed to find evidence of harm were by industry-affiliated authors.

* Delaying and discrediting legitimate research (see for an example of how the industry attempted to discredit Hirayama's landmark study, and for an example of how it attempted to delay and discredit a major Australian report on passive smoking)

* Promoting "good epidemiology" and attacking so-called junk science (a term popularised by industry lobbyist Steven Milloy): attacking the methodology behind research showing health risks as flawed and attempting to promote sound science . Ong & Glantz (2001) cite an internal Phillip Morris memo giving evidence of this as company policy

* Creation of outlets for favorable research. In 1989, the tobacco industry established the International Society of the Built Environment, which published the peer-reviewed journal Indoor and Built Environment. This journal did not require conflict-of-interest disclosures from its authors. With documents made available through the Master Settlement, it was found that the executive board of the society and the editorial board of the journal were dominated by paid tobacco-industry consultants. The journal published a large amount of material on passive smoking, much of which was "industry-positive".

Citing the tobacco industry's production of biased research and efforts to undermine scientific findings, the 2006 U.S. Surgeon General's report concluded that the industry had "attempted to sustain controversy even as the scientific community reached consensus... industry documents indicate that the tobacco industry has engaged in widespread activities... that have gone beyond the bounds of accepted scientific practice." The U.S. District Court, in U.S.A. v. Philip Morris et al., found that "...despite their internal acknowledgment of the hazards of secondhand smoke, Defendants have fraudulently denied that ETS causes disease."[

Passive smoking has played a central role in the debate over the harms and regulation of tobacco products. Since the early 1970s, the tobacco industry has been concerned about passive smoking as a serious threat to its business interests; harm to bystanders was perceived as a motivator for stricter regulation of tobacco products. Despite the awareness of results "strongly suggestive" of harms from secondhand smoke as early as the 1980s, the tobacco industry coordinated a scientific controversy with the aim of forestalling regulation of their products.:1242 Currently, the health risks of secondhand smoke are a matter of scientific consensus, and these risks have been one of the major motivations for smoking bans in workplaces and indoor public places, including restaurants, bars and night clubs.

Secondhand smoke causes many of the same diseases as direct smoking, including cardiovascular diseases, lung cancer, and respiratory diseases. These diseases include:

* Cancer:

o General: overall increased risk; reviewing the evidence accumulated on a worldwide basis, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded in 2004 that "Involuntary smoking (exposure to secondhand or 'environmental' tobacco smoke) is carcinogenic to humans."

o Lung cancer: the effect of passive smoking on lung cancer has been extensively studied. A series of studies from the USA from 1986–2003, the UK in 1998, Australia in 1997 and internationally in 2004 have consistently shown a significant increase in relative risk among those exposed to passive smoke.

o Breast cancer: The California Environmental Protection Agency concluded in 2005 that passive smoking increases the risk of breast cancer in younger, primarily premenopausal women by 70% and the US Surgeon General has concluded that the evidence is "suggestive," but still insufficient to assert such a causal relationship. In contrast, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded in 2004 that there was "no support for a causal relation between involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke and breast cancer in never-smokers."

o Renal cell carcinoma (RCC): A recent study shows an increased RCC risk among never smokers with combined home/work exposure to passive smoking.

o Passive smoking does not appear to be associated with pancreatic cancer.

o Brain tumor: The risk in children increases significantly with higher amount of passive smoking, even if the mother doesn't smoke, thus not restricting risk to prenatal exposure during pregnancy.

* Ear, nose, and throat: risk of ear infections.

o Secondhand smoke exposure is associated with hearing loss in non-smoking adults.

* Circulatory system: risk of heart disease, reduced heart rate variability, higher heart rate.

o Epidemiological studies have shown that both active and passive cigarette smoking increase the risk of atherosclerosis.

* Lung problems:

o Risk of asthma.

* Cognitive impairment and dementia: Exposure to secondhand smoke may increase the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in adults 50 and over.

* During pregnancy:

o Low birth weight, part B, ch. 3.

o Premature birth, part B, ch. 3 (Note that evidence of the causal link is only described as "suggestive" by the US Surgeon General in his 2006 report.)

o Recent studies comparing women exposed to Environmental Tobacco Smoke and non-exposed women, demonstrate that women exposed while pregnant have higher risks of delivering a child with congenital abnormalities, longer lengths, smaller head circumferences, and low birth weight.

* General:

o Worsening of asthma, allergies, and other conditions.

* Risk to children:]

o Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In his 2006 report, the US Surgeon General concludes: "The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between exposure to secondhand smoke and sudden infant death syndrome."

o Asthma

o Lung infections

o More severe illness with bronchiolitis, and worse outcome

o Increased risk of developing tuberculosis if exposed to a carrier

o Allergies

o Crohn's disease.

o Learning difficulties, developmental delays, and neurobehavioral effects. Animal models suggest a role for nicotine and carbon monoxide in neurocognitive problems.

o An increase in tooth decay (as well as related salivary biomarkers) has been associated with passive smoking in children.

o Increased risk of middle ear infections.

* Skin Disorder

o Childhood exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke is associated with an increased risk of the development of adult-onset Atopic dermatitis.

* Overall increased risk of death in both adults, where it is estimated to kill 53,000 nonsmokers per year, making it the 3rd leading cause of preventable death in the U.S. and in children. Another research financed by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and Bloomberg Philanthropies found that passive smoking causes about 603,000 death a year, which represents 1% of the world's death.

Epidemiological studies show that non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke are at risk for many of the health problems associated with direct smoking.

In 1992, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a review of available evidence on the relationship between secondhand smoke and heart disease, and estimated that passive smoking was responsible for 35,000 to 40,000 deaths per year in the United States in the early 1980s. The absolute risk increase of heart disease due to ETS was 2.2%, while the attributable risk percent was 23%.

Research using more exact measures of secondhand smoke exposure suggests that risks to nonsmokers may be even greater than this estimate. A British study reported that exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk of heart disease among non-smokers by as much as 60%, similar to light smoking. Evidence also shows that inhaled sidestream smoke, the main component of secondhand smoke, is about four times more toxic than mainstream smoke, a fact that known to the tobacco industry since the 1980s, which kept its findings secret. Some scientists believe that the risk of passive smoking, in particular the risk of developing coronary heart diseases, may have been substantially underestimated.

A minority of epidemiologists find it hard to understand how environmental tobacco smoke, which is far more dilute than actively inhaled smoke, could have an effect that is such a large fraction of the added risk of coronary heart disease among active smokers. One proposed explanation is that secondhand smoke is not simply a diluted version of "mainstream" smoke, but has a different composition with more toxic substances per gram of total particulate matter. Passive smoking appears to be capable of precipitating the acute manifestations of cardio-vascular diseases (atherothrombosis) and may also have a negative impact on the outcome of patients who suffer acute coronary syndromes.

In 2004, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO) reviewed all significant published evidence related to tobacco smoking and cancer. It concluded:

These meta-analyses show that there is a statistically significant and consistent association between lung cancer risk in spouses of smokers and exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke from the spouse who smokes. The excess risk is of the order of 20% for women and 30% for men and remains after controlling for some potential sources of bias and confounding.

Subsequent meta-analyses have confirmed these findings, and additional studies have found that high overall exposure to passive smoke even among people with non-smoking partners is associated with greater risks than partner smoking and is widespread in non-smokers.

The National Asthma Council of Australia cites studies showing that environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) is probably the most important indoor pollutant, especially around young children:

* Smoking by either parent, particularly by the mother, increases the risk of asthma in children.

* The outlook for early childhood asthma is less favourable in smoking households.

* Children with asthma who are exposed to smoking in the home generally have more severe disease.

* Many adults with asthma identify ETS as a trigger for their symptoms.

* Doctor-diagnosed asthma is more common among non-smoking adults exposed to ETS than those not exposed. Among people with asthma, higher ETS exposure is associated with a greater risk of severe attacks.

In France, passive smoking has been estimated to cause between 3,000 and 5,000 premature deaths per year, with the larger figure cited by Prime minister Dominique de Villepin during his announcement of a nationwide smoking ban: "That makes more than 13 deaths a day. It is an unacceptable reality in our country in terms of public health."

There is good observational evidence that smoke-free legislation reduces the number of hospital admissions for heart disease. In 2009 two studies in the United States confirmed the effectiveness of public smoking bans in preventing heart attacks. The first study, done at the University of California, San Francisco and funded by the National Cancer Institute, found a 15 percent decline in heart-attack hospitalizations in the first year after smoke-free legislation was passed, and 36 percent after three years. The second study, done at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, showed similar results. Overall, women, nonsmokers, and people under age 60 had the most heart attack risk reduction. Many of those benefiting were hospitality and entertainment industry workers.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization concluded in 2004 that there was sufficient evidence that secondhand smoke caused cancer in humans. Most experts believe that moderate, occasional exposure to secondhand smoke presents a small but measurable cancer risk to nonsmokers. The overall risk depends on the effective dose received over time. The risk level is higher if non-smokers spend many hours in an environment where cigarette smoke is widespread, such as a business where many employees or patrons are smoking throughout the day, or a residential care facility where residents smoke freely. The US Surgeon General, in his 2006 report, estimated that living or working in a place where smoking is permitted increases the non-smokers' risk of developing heart disease by 25–30% and lung cancer by 20–30%.

Environmental Tobacco Smoke can be evaluated either by directly measuring tobacco smoke pollutants found in the air or by using biomarkers, an indirect measure of exposure. As of 2005, Nicotine, cotinine, thiocyanates, and proteins are the most specific biological markers of tobacco smoke exposure.

* Cotinine

o Cotinine, the metabolite of Nicotine, is the preferred biomarker of Environmental Tobacco Smoke exposure. Typically, Cotinine is measured in the blood, saliva, and urine. Hair analysis has recently become a new, noninvasive measurement technique. Cotinine accumulates in hair during hair growth, which results in a measure of long-term, cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke.

o Urinary cotinine levels have been a reliable biomarker of tobacco exposure and have been used as a reference in many epidemiological studies. However, cotinine levels found in the urine only reflect exposure over the preceding 48 hours. Cotinine levels of the skin, such as the hair and nails, reflect tobacco exposure over the previous three months and are a more reliable biomarker.

o Cotinine is a much more reliable biomarker of Environmental Tobacco Smoke than surveys. Certain groups of people are reluctant to disclose their smoking status and exposure to tobacco smoke, especially pregnant women and parents of young children. This is due to their smoking being socially unacceptable. Also, recall of tobacco smoke exposure may be difficult. Cotinine measurements are therefore more reliable biomarkers.

In 2007, the Addictive Behaviors Journal found a positive correlation between secondhand tobacco smoke exposure and concentrations of nicotine and/or biomarkers of nicotine in the body. A significant amount of biological levels of nicotine from secondhand smoke exposure were equivalent to nicotine levels from active smoking and levels that are associated with behavior changes due to nicotine consumption.

A 2004 study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization concluded that nonsmokers are exposed to the same carcinogens as active smokers. Sidestream smoke contains more than 4,000 chemicals, including 69 known carcinogens. Of special concern are polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines, and aromatic amines, such as 4-Aminobiphenyl, all known to be highly carcinogenic. Mainstream smoke, sidestream smoke, and secondhand smoke contain largely the same components, however the concentration varies depending on type of smoke. Several well-established carcinogens have been shown by the tobacco companies' own research to be present at higher concentrations in sidestream smoke than in mainstream smoke.

Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) has been shown to produce more particulate-matter (PM) pollution than an idling low-emission diesel engine. In an experiment conducted by the Italian National Cancer Institute, three cigarettes were left smoldering, one after the other, in a 60 m³ garage with a limited air exchange. The cigarettes produced PM pollution exceeding outdoor limits, as well as PM concentrations up to 10-fold that of the idling engine.

Tobacco smoke exposure has immediate and substantial effects on blood and blood vessels in a way that increases the risk of a heart attack, particularly in people already at risk. Exposure to tobacco smoke for 30 minutes significantly reduces coronary flow velocity reserve in healthy nonsmokers.

Pulmonary emphysema can be induced in rats through acute exposure to sidestream tobacco smoke (30 cigarettes per day) over a period of 45 days. Degranulation of mast cells contributing to lung damage has also been observed.

The term "third-hand smoke" was recently coined to identify the residual tobacco smoke contamination that remains after the cigarette is extinguished and secondhand smoke has cleared from the air. Preliminary research suggests that byproducts of thirdhand smoke may pose a health risk, though the magnitude of risk, if any, remains unknown.

In 2008, there were more than 161,000 deaths attributed to lung cancer in the United States. Of these deaths, an estimated 10% to 15% were caused by factors other than first-hand smoking; equivalent to 16,000 to 24,000 deaths annually. Slightly more than half of the lung cancer deaths caused by factors other than first-hand smoking were found in nonsmokers. Lung cancer in nonsmokers may well be considered one of the most common cancer mortalities in the United States. Clinical epidemiology of lung cancer has linked the primary factors closely tied to lung cancer in nonsmokers as exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke, carcinogens including radon, and other indoor air pollutants.

Recent major surveys conducted by the U.S. National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control have found widespread public belief that secondhand smoke is harmful. In both 1992 and 2000 surveys, more than 80% of respondents agreed with the statement that secondhand smoke was harmful. A 2001 study found that 95% of adults agreed that secondhand smoke was harmful to children, and 96% considered tobacco-industry claims that secondhand smoke was not harmful to be untruthful.

A 2007 Gallup poll found that 56% of respondents felt that secondhand smoke was "very harmful", a number that has held relatively steady since 1997. Another 29% believe that secondhand smoke is "somewhat harmful"; 10% answered "not too harmful", while 5% said "not at all harmful".

As part of its attempt to prevent or delay tighter regulation of smoking, the tobacco industry funded a number of scientific studies and, where the results cast doubt on the risks associated with passive smoking, sought wide publicity for those results. The industry also funded libertarian and conservative think tanks, such as the Cato Institute in the United States and the Institute of Public Affairs in Australia which criticised both scientific research on passive smoking and policy proposals to restrict smoking. These industry-wide coordinated activities constitute one of the earliest expressions of corporate denialism. Today, not all criticism comes from the tobacco industry or its front groups: building up on the desinformation spread by the tobacco industry, a tobacco denialism movement has emerged, sharing many characteristics of other forms of denialism, such as HIV-AIDS denialism.

A 2003 study by Enstrom and Kabat, published in the British Medical Journal, argued that the harms of passive smoking had been overstated. Their analysis reported no statistically significant relationship between passive smoking and lung cancer, though the accompanying editorial noted that "they may overemphasise the negative nature of their findings."This paper was widely promoted by the tobacco industry as evidence that the harms of passive smoking were unproven. The American Cancer Society (ACS), whose database Enstrom and Kabat used to compile their data, criticized the paper as "neither reliable nor independent", stating that scientists at the ACS had repeatedly pointed out serious flaws in Enstrom and Kabat's methodology prior to publication. Notably, the study had failed to identify a comparison group of "unexposed" persons.

Enstrom's ties to the tobacco industry also drew scrutiny; in a 1997 letter to Philip Morris, Enstrom requested a "substantial research commitment... in order for me to effectively compete against the large mountain of epidemiologic data and opinions that already exist regarding the health effects of ETS and active smoking." In a US racketeering lawsuit against tobacco companies, the Enstrom and Kabat paper was cited by the US District Court as "a prime example of how nine tobacco companies engaged in criminal racketeering and fraud to hide the dangers of tobacco smoke." The Court found that the study had been funded and managed by the Center for Indoor Air Research, a tobacco industry front group tasked with "offsetting" damaging studies on passive smoking, as well as by Phillip Morris who stated that Ernstrom's work was "clearly litigation-oriented." Enstrom has defended the accuracy of his study against what he terms "illegitimate criticism by those who have attempted to suppress and discredit it."

A 1998 report by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) on environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) found "weak evidence of a dose-response relationship between risk of lung cancer and exposure to spousal and workplace ETS."

In March 1998, before the study was published, reports appeared in the media alleging that the IARC and the World Health Organization (WHO) were suppressing information. The reports, appearing in the British Sunday Telegraph and The Economist, among other sources, alleged that the WHO withheld from publication of its own report that supposedly failed to prove an association between passive smoking and a number of other diseases (lung cancer in particular).

In response, the WHO issued a press release stating that the results of the study had been "completely misrepresented" in the popular press and were in fact very much in line with similar studies demonstrating the harms of passive smoking.The study was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in October of the same year. An accompanying editorial summarized:

When all the evidence, including the important new data reported in this issue of the Journal, is assessed, the inescapable scientific conclusion is that ETS is a low-level lung carcinogen.

With the release of formerly classified tobacco industry documents through the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, it was found that the controversy over the WHO's alleged suppression of data had been engineered by Philip Morris, British American Tobacco, and other tobacco companies in an effort to discredit scientific findings which would harm their business interests. A WHO inquiry, conducted after the release of the tobacco-industry documents, found that this controversy was generated by the tobacco industry as part of its larger campaign to cut the WHO's budget, distort the results of scientific studies on passive smoking, and discredit the WHO as an institution. This campaign was carried out using a network of ostensibly independent front organizations and international and scientific experts with hidden financial ties to the industry.

The passive smoking issue poses a serious economic threat to the tobacco industry. It has broadened the definition of smoking beyond a personal habit to something with a social impact. In a confidential 1978 report, the tobacco industry described increasing public concerns about passive smoking as "the most dangerous development to the viability of the tobacco industry that has yet occurred." In United States of America v. Philip Morris et al., the District Court for the District of Columbia found that the tobacco industry "... recognized from the mid-1970s forward that the health effects of passive smoking posed a profound threat to industry viability and cigarette profits," and that the industry responded with "efforts to undermine and discredit the scientific consensus that ETS causes disease."

Accordingly, the tobacco industry have developed several strategies to minimize its impact on their business:

* The industry has sought to position the passive smoking debate as essentially concerned with civil liberties and smokers' rights rather than with health, by funding groups such as FOREST.

* Funding bias in research; in all reviews of the effects of passive smoking on health published between 1980 and 1995, the only factor associated with concluding that passive smoking is not harmful was whether an author was affiliated with the tobacco industry. However, not all studies that failed to find evidence of harm were by industry-affiliated authors.

* Delaying and discrediting legitimate research (see for an example of how the industry attempted to discredit Hirayama's landmark study, and for an example of how it attempted to delay and discredit a major Australian report on passive smoking)

* Promoting "good epidemiology" and attacking so-called junk science (a term popularised by industry lobbyist Steven Milloy): attacking the methodology behind research showing health risks as flawed and attempting to promote sound science . Ong & Glantz (2001) cite an internal Phillip Morris memo giving evidence of this as company policy

* Creation of outlets for favorable research. In 1989, the tobacco industry established the International Society of the Built Environment, which published the peer-reviewed journal Indoor and Built Environment. This journal did not require conflict-of-interest disclosures from its authors. With documents made available through the Master Settlement, it was found that the executive board of the society and the editorial board of the journal were dominated by paid tobacco-industry consultants. The journal published a large amount of material on passive smoking, much of which was "industry-positive".

Citing the tobacco industry's production of biased research and efforts to undermine scientific findings, the 2006 U.S. Surgeon General's report concluded that the industry had "attempted to sustain controversy even as the scientific community reached consensus... industry documents indicate that the tobacco industry has engaged in widespread activities... that have gone beyond the bounds of accepted scientific practice." The U.S. District Court, in U.S.A. v. Philip Morris et al., found that "...despite their internal acknowledgment of the hazards of secondhand smoke, Defendants have fraudulently denied that ETS causes disease."[

No comments:

Post a Comment